Much has been written lately about the converging crises threatening to upend the enrollment operations at traditional four-year undergraduate colleges and universities.

In a nutshell, here’s where we’re at: a decreasing number of students are being courted by increasingly nervous institutions whose net revenue is trending down and whose published cost of attendance is trending up. These tensions coincide with growing public sentiment that college is too expensive and the returns on a college degree too unclear.

At many regional publics and small privates, these realities have long been a fact of life. A report in last week’s Chronicle made the case, however, that historically “stronger,” more selective schools may not be as immune as previously thought from these same disruptions.

I’d argue that the problems faced by this latter group are of a different variety and urgency—and will be for some time—than those facing smaller, less-well-known schools. But regardless of institution type, one similarity unites them, and that is that inside the organization, the first person to feel heat for any real or perceived revenue-related shortcomings will be the vice president of enrollment.

Blame-casting is a fact of life in industries of all types, but what seems especially unfortunate to me about the way some VPs end up getting treated in our industry is that they’re ultimately held accountable—and subsequently fired—for things they didn’t know they were responsible for or for failing to meet goals they were never truly empowered to reach.

In fact, it seems to me, that there is broad misunderstanding in our industry about what a vice president of enrollment actually does and should do.

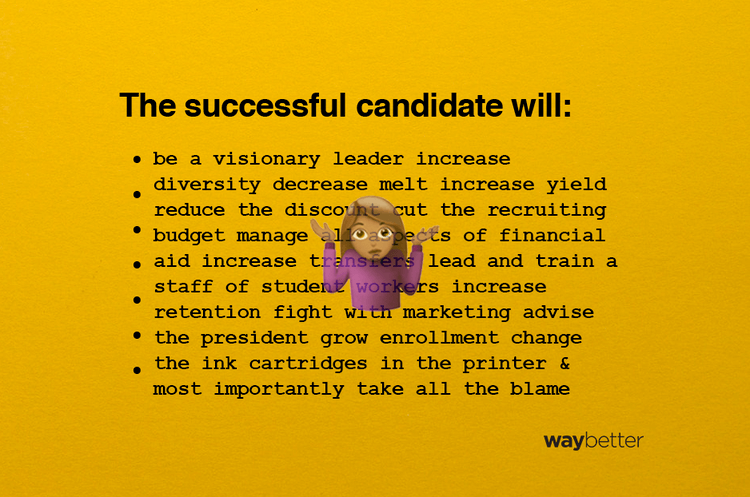

But before I go on, please understand me: I’m not saying that VPs of enrollment don’t understand what their jobs are. What I’m saying is that what their jobs entail—and sometimes the absolute and most crucial aspects of what their jobs entail—are not frequently the things they end up getting asked to do on a day-in, day-out basis at the colleges and universities they work for.

Between the conversations I’ll have on my campus visits to Waybetter clients this year, and the dozens more chief enrollment officers I’ll speak with at industry events, it will be impossible to not notice the similarities among those who find themselves struggling with this dissonance—impossible not to see how even the smartest, most talented, most enthusiastic enrollment managers are battered off course by waves of internal politics, project creep, underfunding, executive delusion, and all manner of other distractions that keep them from doing the most important thing they were brought there to do in the first place: improve the institution’s financial position through the intake of tuition revenue.

Here’s how, after a decade working exclusively for colleges and universities of all types, I’ve come to view the job of a vice president of enrollment…

The Vice President of Enrollment is the Vice President of Sales

I know I’m not the first to make this comparison—but when I hear others make it, they never quite follow through to the full implications. I also know that some folks in higher ed bristle at the comparison of enrollment to sales. They feel it’s too commercial, too mercenary a way to talk about the noble business of education. I understand the objection, and in my own way I agree with it, but it’s also my hard-won belief that VPs of enrollment who can conceive of their role in this way have more success than those who can’t or won’t.

And that’s simply because at organizations of all shapes and sizes all over the world, the VP of sales is the engine that makes commerce possible. And colleges and universities, especially those most susceptible to shifting demographic trends, must have a person dedicated to this pursuit—to generating enough revenue to keep the enterprise alive and thriving. In other industries, this reality isn’t sugarcoated. In fact, it’s often right there in the first sentence of the job’s requirements.

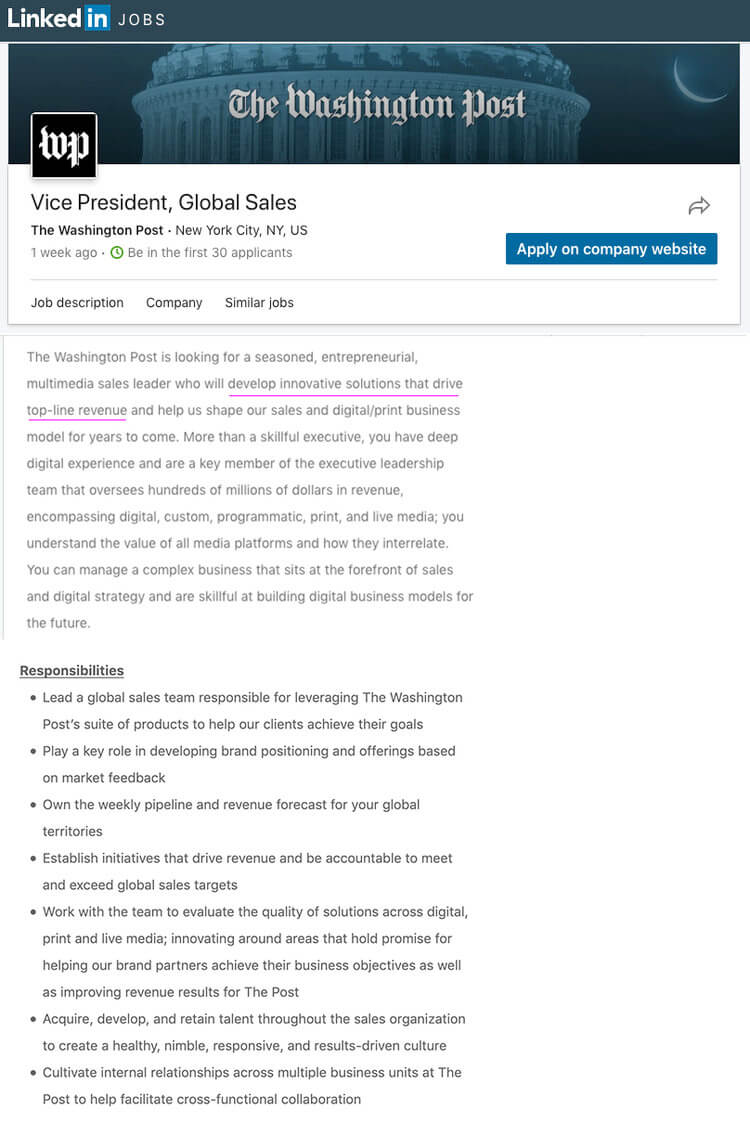

To illustrate more fully what I mean, consider The Washington Post’s recent listing for a vice president of sales.

There it is in black and white (and underlined in purple): drive top-line revenue. I’ve never seen a position for a VP of enrollment that included that line so clearly, let alone in the opening sentence—even though the presence of revenue, or its absence, is almost always the single determining factor in whether an enrollment VP gets to keep their job. This is something we all know but rarely address so directly in formalized ways.

That’s crazy… right?

Institutions that have been stunned to attention by the cold realities of the new demographic ecosystem are bit clearer in their expectations, but not much. And even when they are, the same focus-destroying facts of institutional bureaucracy threaten to undermine and obscure those expectations.

So, I’ll say it again: if you’re a VP of enrollment, your single most important priority is driving revenue. Notice I didn’t say “being a good leader” or “increasing retention” or even “enrolling more students.” All those things might add up to increased net revenue, but they’re also obscuring proxies for the real thing—for the real clear language that drives the mission and requisite urgency.

The Vice President of Sales Is Connected to Every Facet of the Organization

In higher ed, the VP of enrollment often has limited interaction with—and sometimes limited visibility into—the other “business” units of the university. They’re often left out of what may be important decisions regarding new product offerings. Or they don’t have visibility into the marketing operations that are, ostensibly, helping them generate interest for their offerings. Or they’re left out of decisions regarding tuition and pricing maneuvers.

Take another look at the Washington Post description. The sales VP they hire will have access to every single facet of the organization, including determining what products they’ll actually be creating and selling and growing more of, and marketing, and human resources. This is standard operating procedure.

VPs of enrollment need to find ways to force their way into these conversations on their campuses. But this is where higher ed’s rigid ways often interfere with its own best interests. The academic side of the house frequently rejects attempts to make more market-friendly programs (or to make popular programs bigger). Marketers frequently prioritize “building the brand” over collaborating in meaningful ways with the enrollment team on brand-building activities that also assist enrollment.

For some VPs of enrollment these barriers can feel built-in, elemental—part and parcel of the air they have to breathe. But of course that’s not the case. It may (it will) be difficult to bend other people and their long-held ways of being to your will, but you can insert yourself and try to own at least parts of these conversations. In fact you must, because they’re all factors in what will eventually be the revenue you do or don’t bring in.

For an example of what this looks like in practice, I’d encourage you to read this interview with the enrollment leaders at Husson University in Bangor, Maine. Pay special attention to the part about how they convinced the directors of their popular health sciences programs to accept more students.

In the end, it really becomes a matter of how much you’re willing to push.

The Vice President of Sales is the “Chief Pusher In Charge”

If you’re responsible for the revenue an organization generates, you have to develop a mindset that helps you harness—through sheer will and force of personality if necessary—all the revenue-generating facets of the operation. At a university, this includes, among others: the president, the financial aid office, the marketing office, and even the faculty.

Part of this harnessing, which sounds easy enough in theory, is that you must be willing to resist the demands these others will seek to put on you. Yes, you must be a good colleague to them, but you can’t allow them to chart your course. Instead, you must find a way to chart theirs. Here’s an example of what I’m talking about:

I talked recently with a VP of enrollment who’s come out the other side of some very difficult professional situations. Situations that she survived and eventually thrived in and then parlayed into a job that was a better fit at a healthier institution.

She told me that one thing she’d learned was to never, ever sacrifice her or her department’s resources for the “greater good.” So when her new president asked her to eliminate an admissions counselor position as part of across-the-board budget cuts, she knew the long-term damage of that decision would far outweigh any short-term benefit. So she fought, and along the way risked alienating her new president as well as her cabinet colleagues who were all being good team players and consenting to the cuts. It was a risk she was willing to take. And then she had the nerve to ask for a budget increase.

What she’d learned in previous roles, she said, was that she knew she could be fired for missing her enrollment and revenue goals, and that she wouldn’t be saved by polite acquiescence. She had to learn to push, in ways that will always conflict with her otherwise easygoing personality.

I also talked recently with an enrollment team whose lives were being made miserable by a financial aid office that was, for reasons that are still unclear, not packaging admitted students with any urgency—not even after May 1. Without direct oversight of financial aid, they had to push—they were losing students who wanted to come but couldn’t commit because they didn’t know what the cost would be. This was disastrous for the university’s bottom line—for the next four years. Again, the solution was to take a hard line with people who had often been genial colleagues in the past. Because that enrollment team knows the same truth we all do, which is that it isn’t the financial aid people who get fired first when revenue falls short.

Enrollment VPs must also push their marketing departments—must help them focus on the things that truly matter. I hear frequently from enrollment teams who feel hamstrung by their colleagues in the marketing office who place too much focus on the aesthetics of “brand” communication. For example, these marketers will invest time and energy making the website “look good,” but that same website won’t make it easy for prospective students to request more information, or to find information about how to visit campus, or even to apply! Enrollment leaders must risk ruffling some feathers in order to make sure marketing is supporting their mission in tangible, bottom-line ways.

Enrollment VPs must push the faculty (yes, even the faculty). The schools I’m aware of that are having the most enrollment success get support from enthusiastic faculty who are eager to help in myriad ways, who will listen to proposals for growing popular offerings, who will meet with students and families when they come to campus for a visit, who will agree to be featured on the website and in marketing materials. I understand that faculty may not feel that “recruitment” is part of their job, but the truth is that many of their jobs depend on the success of the enrollment office, and there are real and tangible things they can do to help.

Sales VPs are well versed in the art of pushing—they push their product managers to build to client specifications, the push the finance team to structure the deal to the clients’ needs, they push HR to hire and appropriately compensate the best sales staff, they push marketing to produce assets that do at least a little of the heavy lifting. Without a VP of sales’ pushing all these levers, commerce becomes less possible, and that’s not a reality they’re willing to live with.

The Vice President of Sales Never Wins (Not Even When They Win)

When you’re the chief enrollment officer, you quickly come to realize that even though your job title indicates otherwise, everyone else on campus actually knows more about enrollment than you do.

So even if you hit your numbers, you’ll find people on campus who want to know why you didn’t get even more students, generate even higher net tuition revenue—oh and also improve the academic profile of the class, and also lower the admit rate, and also achieve higher yield, and also lower the discount, and on down the line. It really can come to feel like a no-win situation.

Many VPs of enrollment I know are naturally drawn to their work because they believe in education, they love helping students find their way toward a rewarding adulthood, and they’re naturally gifted socially. So the hard realities of the job sometimes weigh especially heavy on them, chipping away against much of what they value and hold dear—their altruism, their generosity, their desire for all parties to achieve a desirable outcome (even though they know deep down that generosity and altruism are most possible when hard-earned financial resources allow for it).

So it comes as a bit of a shock their first time through a turbulent cycle to find that even when they’ve done the near-impossible and hit their enrollment and revenue targets, there’s still discord to spare.

This discord can come in many forms. Maybe the discount ticked up a point and the finance office is unhappy. Maybe the student profile ticked down by a tenth of GPA point and the faculty are up in arms. Maybe too many incoming residential students forced student affairs to hire a couple more RAs. And on and on.

And that’s all OK! Eventually you’ll learn to live with—and take great pride in—some hard-won truths of your own. You’ll know how bad it could have been. How much you did to ensure the livelihoods and job safety of your colleagues. How much your healthy college will now contribute to the economy of the town your college calls home. How being successful can allow the school to help those students most in need. These are real victories, and they belong to you, even if they’re not so visible to others.

And that’s what real perseverance over the long term looks like in this line of work—following your own compass because you know it’s the way to help get everyone who’s depending on you where they want to be.

They Need Support, And They Ask For It

Early this spring I introduced to each other three relatively young, early-career VPs of enrollment whom I’ve gotten to know over the years. They were all going through fairly difficult stretches at their respective schools, and they needed the support of people who would understand their dilemmas, and I thought they could help each other out a little.

One of them recently wrote to me that they were glad to be in contact with each other because they’d started a “soul-saving April email chain” that allowed them to vent, to ask for advice, and to simply share their experiences of stress as they approached the May 1 deposit “deadline” a couple weeks ago.

I say this only because I know that doing some of the hard work required of a VP can be isolating. You can feel alone and lonely. But it’s important to remember that you’re not, and that reaching out to others in your field can be rejuvenating and affirming—whether you’re a seasoned pro or just starting out. You’re in a long proud line of people who’ve put their good business sense into the service of a mission they believe in.

So keep fighting the good fight! Your instincts are good, your compass is true—the voice in your head will help you push and fight for what you know is right.