1. It Takes A College

Despite the fact that I’ve been in higher ed my entire professional life, I hadn’t heard of summer melt until a couple years ago when the college where I worked as director of marketing and communications lost 102 deposited students between May 1 and the start of the fall semester.

Go ahead and let that sink in…102 deposited students. That was 19% of our incoming undergraduate class, and, as you can imagine, it wreaked all kinds of havoc all over the college (budget projections went to hell, morale plummeted, tumbleweeds drifted through empty residence halls, etc.).

As a small, tuition-dependent private college, we simply couldn’t weather too many more admissions cycles like that, so our president convened a melt task force comprised of folks from across the college—academics, admissions, financial aid, marketing, student affairs, IT, the business office, student accounts, the registrar’s office, and athletics all had seats at the table—and asked us to perform a steely-eyed postmortem and then, using what we learned, collaborate on a cure for what ailed us. Gathering around the same literal table was a necessary first step.

2. Name the No-shows

My colleagues from around campus were genuinely helpful, but a bulk of the early work of course fell to the admissions team. First on their list was to suss out what types of students we lost and why. After all, we had to know who was melting before we could game plan a way to keep them. It turns out, however, that it’s not all that easy to track what happens to students when they blip off your radar. Some of them end up at different colleges and are eventually trackable through the National Student Clearinghouse, but many just seemingly disappear.

A heroic dive into the data by our director of undergraduate admissions, Jon Scully, confirmed as much: our melted students weren’t ditching us for some other college, they simply weren’t going to college at all. Further analysis also revealed that these students belonged to at least one of the following demographics. They were:

- non-white

- Pell-eligible

- first-generation college students

- from our local recruiting area

3. Reframe the Failure (Make it Personal)

While we were glad to understand more about the types of students who slipped away, the realization was also stomach churning. How could we be failing the exact types of students our college had historically served so well? The types of students who would thrive most in the supportive, hands-on, welcoming atmosphere we’d worked so hard to foster? The types of students whose lives would be most profoundly improved by a college education?

It was not an easy realization, for any of us. First, we’d taken a professional hit by falling short of our enrollment target, and then we took a personal gut punch as we came to understand the real scope of our failure. These students hadn’t melted away—they’d found their way to us, and we simply hadn’t held them close enough in their time of need. We suddenly felt like this poor guy from The NeverEnding Story.

4. If You Want to Help Someone, You Gotta Get to Know Them

If you’ve had any reason at all to research summer melt, then nothing that we discovered will surprise you. The stats, of course, aren’t pretty (10–40% of low-income students melt nationally). But from my perch in the marcom office, stats weren’t going to help. I realized I didn’t know nearly enough about the population of students we were failing. So I set out to learn.

Far and away the most valuable resource I found is the book Summer Melt by Benjamin Castleman and Lindsay Page. While largely an exploration of the melt phenomenon from the perspective of high school counselors and their students, it should be required reading for higher ed. enrollment and marketing professionals who truly want to understand what it’s like for high school graduates who want to go to college but just can’t seem to get there.

One of the book’s main findings is that low-income college-intending seniors enter a kind of no-man’s land after high school graduation. During senior year, with help from hands-on teachers and counselors, they managed to apply and get accepted to at least one college. And thanks to eager college admissions counselors, they were always just a phone call away from helpful info about deadlines or transcript submissions or financial aid. But in the summertime? That’s an entirely different ballgame.

“It may seem obvious to you, but for me it was a real breakthrough: summer melt happens in summer for a reason.”

5. Mind the Gap

After graduation, students’ help from high school staff naturally disappears. And if a college is already counting a student as having deposited, she gets routed out of the admission office’s comprehensive communications strategy and “handed off” to other areas on campus. So, very suddenly, the two groups of adults who have been actively supporting and tracking a student’s college journey are suddenly, poof, gone. So…who steps in to fill the gap? And what types of communication were students getting from my non-admissions, non-marketing colleagues after we’d collectively done our job of getting them to enroll? Good questions.

The short answer is that, at our institution at least, incoming students were getting a little bit from a bunch of different people. Student affairs, the registrar, financial aid, student accounts…you name it, everyone got their licks in. And while they had good reasons for contacting these students, suddenly the cohesive communications that emanated from the marcom and admissions offices were replaced by scattershot one-offs from strangers these students had never heard from. It was probably overwhelming in both frequency and content, especially with no centralized point of contact where students could turn with questions.

We also had to acknowledge a tough truth our research revealed about students most at risk for melting: many of them don’t have much help at home. Their parents, having not gone to college themselves, may be just as overwhelmed by the college process as the students are, or there might be language barriers, or maybe there just isn’t the expectation that college is a realistic goal. That’s why the help from high school counselors and college admissions counselors had been such a boon, and that’s why the summer gap was so damaging, especially when things like, you know, the actual bill for college started showing up in the mail.

I can’t stress enough the importance of truly trying to empathize with students who get their first bill from college in summer with, in some cases, no help from adults to wade through it. Imagine yourself at 18, solely responsible for trying to figure out what you owe and then actually making a payment. Would it, just maybe, seem like college wasn’t really meant for you after all?

Which brings us to point number six.

6. Rewrite and Redesign Your College’s Bill

Once we got our heads around the sad fact that our students weren’t able to count on at-home help as much as students not at risk for melting, we knew that whatever we communicated to them after they deposited had to be crystal clear and easy to understand. More importantly, we had to let them know we were still there for them even though it was the middle of summer.

Spoiler alert: We were ultimately able to drastically reduce our melt problem by 30%. And I think the biggest part of that turnaround, by far, was when our dean of admissions at the time, Janelle Holmboe, thought to ask a question that I can’t believe hadn’t been asked a million times already—“So, um, has anyone even seen the bill we send out?” No, in fact, we had not.

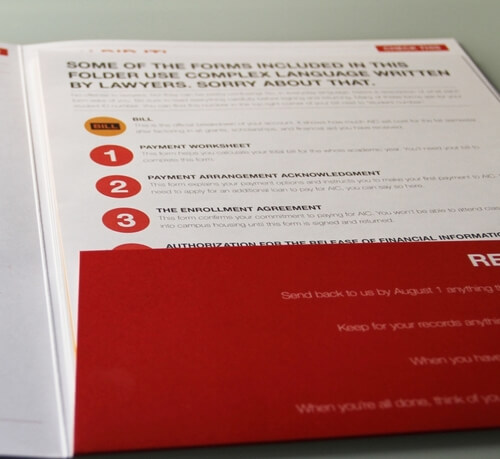

It turns out that our college’s bill had, over the years, come to resemble some kind of ancient scroll that had been passed down through the ages and been amended and appended and photocopied to the point of being reduced to literal and meaningless pulp. It was a mess. It consisted of about 10 different pieces of paper with absolutely inscrutable instructions for how students should calculate and make their first payment, and hard-to-read legal forms like insurance waivers and enrollment agreements. It was terrible. I’ve taught writing and literature in colleges for over a decade, and I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. I’m not kidding.

So, we scrapped it. While we couldn’t change the actual single-page bill itself because of the way it integrated with our student information system, we set to work rewriting and redesigning everything that surrounded it. I’ll write another post about how exactly we went about doing this, but I’m not exaggerating when I say that our finished product is, to this date, the thing I’m most proud of as a communications professional (Bill Cunningham, the art director on the project, has some pics up on his site). We took something that was hard to understand and made it consumable and helpful and functional.

In fact, the bill was so successful with first-year students that our student accounts office asked us to create a version to use for returning students, too.

7. Do What You Can (You Can Do A Lot!)

All told, it took us about a month to redo the bill. And it was tough. Coordinating with about four different offices took time, tact, and patience. If you don’t have that amount of time (or easy access to a writer and a designer), there are still a few things you can do—today—to improve the effectiveness of your bill and start beating summer melt.

First, as often as possible in the actual billing packet, let students know that you get what they’re going through and that you’re there to help. At several different places in our new bill (on the folder it came in, in the introductory letter, and anywhere else we could fit it) we let students know that it was OK to be concerned about paying for college and gave them direct phone numbers to financial aid staff members who could help.

Start texting. Your current admissions CRM might have this ability. If it doesn’t, or if you don’t have the staff to manage it, reach out to us and we’ll be happy to point you toward some solutions. Research bears out that students respond to texts very quickly, compared to email and phone calls. Send a couple messages in the summer. Ask if students have questions. Tell them you’re there to help.

Make a couple videos. They don’t have to be polished or professional. Your iPhone will do just fine. Find a couple current, first-generation students on your campus and ask them to address the incoming class. Try to get them to talk about the fears and insecurities they dealt with the summer before enrolling and how they overcame them. Email these videos to your whole accept pool, or even just those you’ve identified as being at risk for melting. You’ll be shocked at how heartfelt and effective these simple messages can be (even still, keep the videos under a minute).

8. Stay the Course

Melt keeps students who want to go to college out of college. They’ve deposited, they’ve committed, they want to come. But those long summer months play mind games. Students worry they can’t succeed in college. They worry they won’t be able to pay for college. They lack the support that so many other college-intending students have. We have a moral obligation to help them get to where they want to go.

I’ll leave you with a final bit of reading that profoundly affected the way I think about students for whom college feels like a long shot. This piece in the New York Times a couple years ago paints an extraordinary picture of the challenges that many non-white, first-generation college students face as they set out to make a college degree a reality. It’s mostly about retention, but the implications for admissions and marcom staffs should be obvious.

Finally, don’t worry if you can’t make all the changes at once. Just do a little bit at a time. And get in touch with us if you want a little advice—about summer melt or any other enrollment issue.

Joel Anderson is Waybetter’s VP of Marketing & Strategy. Higher ed is all he knows.